Yellowstone has erupted three times in the past 2.1 million years, and each event buried large portions of North America under ash. The last one happened 640,000 years ago, a fact news outlets love to mention alongside coverage of earthquake swarms and steam explosions. The framing is always the same. Are we overdue? Mike Poland hears it constantly. “Volcanoes don’t work like that,” says Poland, who runs the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. “They erupt when there’s enough magma to erupt and enough pressure to push it to the surface. Right now, Yellowstone has neither.”

How a Supervolcano Works

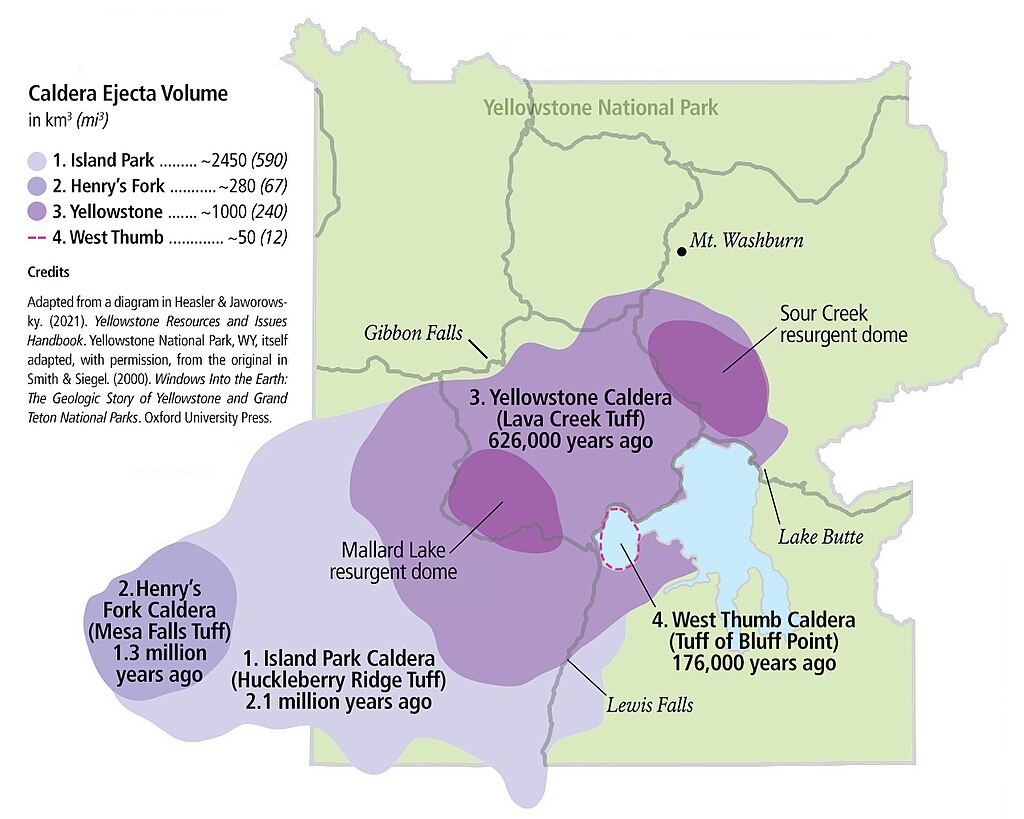

Most volcanoes build themselves up over time, adding layers of lava until a cone takes shape. Supervolcanoes work in reverse. They form when a magma chamber grows so large and erupts so violently that the ground above collapses, leaving behind a bowl-shaped depression called a caldera. Yellowstone’s caldera stretches 45 miles across, so vast that visitors standing on one rim cannot see the other side. The last eruption expelled roughly 240 cubic miles of material, about 1,000 times the volume of Mount St. Helens in 1980. For an eruption of that scale to happen again, Poland says, the system would need far more mobile magma than current monitoring suggests exists.

What Lies Beneath Yellowstone

Yellowstone sits on two massive magma reservoirs, the upper one holding enough partially molten rock to fill the Grand Canyon twice over, and the deeper one more than 11 times. That heat warms groundwater circulating through cracks in the rock, feeding more than 10,000 geysers and hot springs at the surface. For years, seismic images of those chambers looked blurry, but in 2025, researchers used artificial seismic waves to map the reservoir’s upper boundary for the first time. “It’s sort of like taking an MRI of the Earth,” Poland says. The images showed that the upper chamber is roughly 86% solid rock, with the remaining pore spaces venting gas through features like Old Faithful rather than building pressure.

The Monitoring Network

Yellowstone is one of the most closely watched volcanoes on Earth, monitored by a consortium of nine federal, state, and academic agencies called the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. GPS stations track ground movement down to fractions of an inch while tiltmeters measure how the surface bends in response to pressure shifts below. Gas sensors sample emissions from fumaroles for chemical changes that might indicate fresh magma rising toward the surface, and satellites image the caldera from orbit to catch inflation or deflation invisible from the ground. Scientists at the University of Utah watch the data in real time, and if Yellowstone were building toward an eruption, the signs would show up here first.

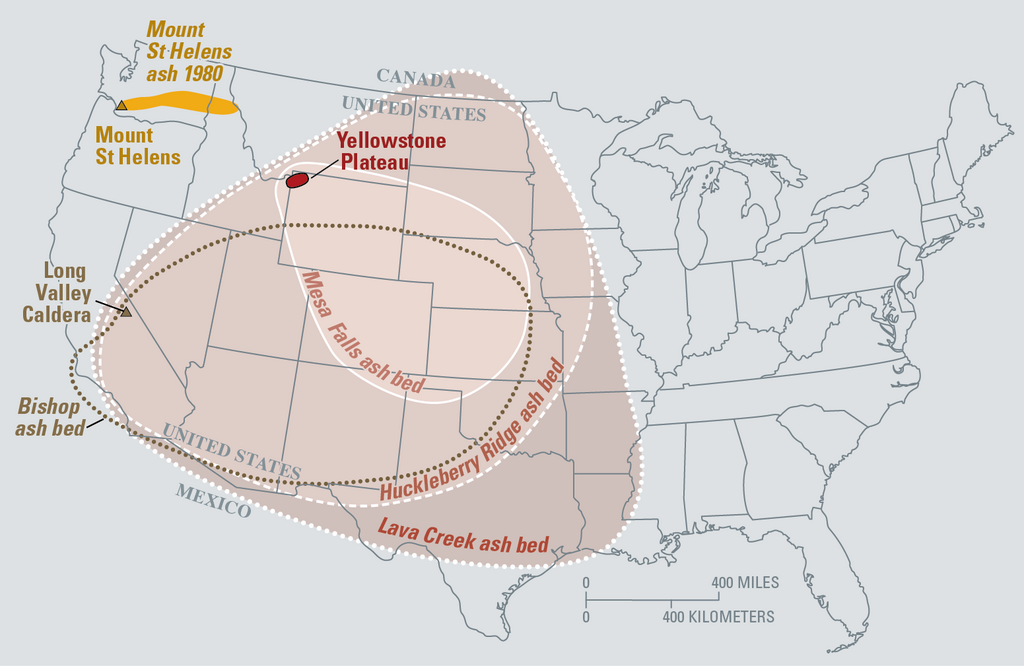

The Three Massive Eruptions

Yellowstone has produced three caldera-forming eruptions in the past 2.1 million years. Colin Wilson, a volcanologist at Victoria University of Wellington, has spent two decades studying these deposits and found that each eruption unfolded in phases over weeks or even decades. The first and largest, 2.1 million years ago, ejected roughly 590 cubic miles of material. The second, 1.3 million years ago, was the smallest at 67 cubic miles, and the most recent came 640,000 years ago at 240 cubic miles, creating the caldera visitors walk through today. News coverage likes to note that the average interval is about 725,000 years, but three data points are not enough to establish a pattern.

Recent Seismic Activity

Earthquakes happen constantly at Yellowstone, typically ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 per year, and most are too small for anyone to feel. They occur because the volcanic system is always adjusting, with fluids moving underground and stress building and releasing along fault lines. In July 2025, a team led by Western University engineering professor Bing Li published a study in Science Advances using machine learning to re-examine 15 years of seismic data from the caldera, and they detected approximately 10 times more seismic events than previously recorded. The older detection methods had simply missed them. More earthquakes don’t mean more danger. It means better instruments and smarter analysis.

The Last Time It Blew

Ash from that final eruption spread across 21 states and reached southern Canada and northern Mexico, with deposits sitting half a meter thick even 1,000 miles from the caldera. Closer to the source, pyroclastic flows swept outward at hundreds of miles per hour, superheated clouds of gas and rock that piled so deep the material fused into solid sheets more than 1,300 feet thick. So much magma emptied from the chamber that the ground above it collapsed, and the caldera walls left behind still rise 1,600 feet above the valley floor. The mountains that once stood where Yellowstone Lake now sits fell into the emptied chamber below.

Why People Fear Another Blast

The fear took hold in 2000, when a BBC documentary introduced the word “supervolcano” to a mass audience and planted Yellowstone at the center of it. Five years later, the BBC and Discovery Channel followed with a $5.5 million docudrama that depicted the park exploding, ash clouds racing across the country, and civilization grinding to a halt. The film was marketed with the tagline “A true story of global disaster, it just hasn’t happened yet.”

Since then, every earthquake swarm and steam vent has become headline material, and searches for “Yellowstone doomsday” return hundreds of thousands of results. The math sounds ominous, too. Three eruptions over 2.1 million years work out to an average interval of about 725,000 years, and the last one was 640,000 years ago. But averages built from three data points tell you almost nothing about when the next event will come, and scientists who actually monitor the system say there is no evidence one is brewing.

The November 2025 Numbers

During November 2025, the University of Utah Seismograph Stations located 251 earthquakes in the Yellowstone region, with the largest being a magnitude 3.2 event about 14 miles south-southwest of Mammoth Hot Springs. Three separate earthquake swarms contributed to that count, including an ongoing sequence that started in late September and has since added 70 more earthquakes, and a cluster of 11 near West Yellowstone over Thanksgiving weekend. The observatory characterized all of this as slightly above background levels, which, for Yellowstone, still counts as normal. The ground is always moving.

In late November 2025, small hydrothermal eruptions occurred at Black Diamond Pool in Yellowstone’s Biscuit Basin, and webcam footage captured steam and water shooting into the air. This followed a larger explosion at the same basin in July 2024 that sent tourists running and temporarily closed the area. These events look dramatic, but they’re not volcanic eruptions. Hydrothermal explosions happen when superheated groundwater flashes to steam faster than it can escape through cracks in the rock, and they don’t involve magma reaching the surface. They’re dangerous if you’re standing nearby, but they say nothing about what the deeper system is doing.

Earthquake swarms are clusters of seismic events that occur in the same area over a relatively short period. They’re caused by underground fluids pushing through cracks in the rock. One small rupture creates enough stress to trigger the next, so swarms tend to spread and shift across a localized area over days or weeks before quieting down. Scientists track them because the timing and location of each quake tell them where fluids are moving and how stress is being released. Swarms are not warning signs of an eruption.

What Scientists Actually Found

Despite all the seismic activity and hydrothermal explosions, the official volcanic alert level for Yellowstone has remained at Normal, the lowest category on a four-level scale. Continuous GPS stations recorded little net deformation over the past several months, meaning the ground rose and fell with the seasons but ended up roughly where it started. Earthquake activity, while slightly above background, hasn’t shown the kind of acceleration that would concern volcanologists. The monitoring network designed to catch warning signs isn’t catching any. Yellowstone is restless, but it’s not waking up.

The January 2025 Study

In January 2025, researchers published a new analysis in Nature that mapped exactly what’s happening beneath Yellowstone’s surface. A team from Rice University and three other institutions sent artificial seismic waves into the ground and used the echoes to build a three-dimensional picture of the magma reservoir. They found a sharp, gas-rich cap sitting just 2.4 miles below the surface, and this cap acts like a lid that traps pressure and heat beneath it. Scientists had suspected something like this existed, but now they could actually see it.

The study found that Yellowstone’s magma reservoir is actively releasing gas while remaining stable. Brandon Schmandt, a Rice University geophysicist who helped lead the research, explained that the system vents gas efficiently through cracks and channels between mineral crystals. All those geysers and hot springs that tourists travel to see are evidence of this process at work. The volcanic system has built-in relief valves, and they’ve been functioning for thousands of years without producing an eruption. Pressure builds, gas escapes, and the ground adjusts.

What the Alert Levels Show

Schmandt compared the system to steady breathing, with bubbles rising and releasing through porous rock in a continuous cycle. Researchers did detect a gas-rich layer beneath the surface, but the amount of melt mixed in falls well short of what would signal an approaching eruption. The magma reservoir is mostly solid, not a churning lake of molten rock ready to explode. Think of it like a pot on low simmer with the lid cracked open. The heat escapes gradually instead of building toward a catastrophic release.

The USGS maintains a four-level alert system for volcanoes ranging from Normal to Advisory to Watch to Warning, and Yellowstone has remained at Normal through all the recent seismic swarms and hydrothermal explosions. The Aviation Color Code has stayed at Green, the lowest level, meaning pilots face no ash hazards. After the November 2025 hydrothermal eruptions at Black Diamond Pool, the observatory specifically noted that both indicators remained at their lowest settings. The people whose job is to worry about Yellowstone are not worried.

Tens of Thousands of Years of Nothing

Mike Poland, the scientist in charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, describes the system’s history as a rhythm most people don’t understand. “There are several lava flows, and then tens to hundreds of thousands of years of nothing,” he says. “Then several lava flows, and tens to hundreds of thousands of years of nothing. Right now, we’re in one of those periods of tens to hundreds of thousands of years of nothing.” The last lava flow happened about 70,000 years ago. Poland has also been vocal about disliking the term supervolcano, arguing that it implies the system only produces massive explosions when, in fact, there have been about 80 lava flows since the last catastrophic eruption. “That’s the way these volcanoes mostly behave,” he says.

The Most Likely Scenario

If Yellowstone does produce volcanic activity at some point in the distant future, Poland says it probably won’t be the civilization-ending explosion that dominates headlines. A lava flow is the most likely form of any future activity, and even that remains extremely unlikely. The magma chamber is predominantly solid, and the liquid portion that does exist isn’t large enough to fuel the kind of eruption people fear. The Hollywood version of Yellowstone destroying America isn’t supported by what scientists actually observe underground.

Yellowstone makes for irresistible disaster content. A supervolcano capable of continent-wide destruction sitting under a beloved national park writes its own headlines. Every earthquake swarm becomes potential evidence that the big one is coming, and every hydrothermal explosion gets framed as a warning sign. News outlets know that fear drives clicks, so they emphasize the catastrophic possibilities while glossing over the science that contradicts them. The BBC, National Geographic, and countless other outlets run stories about Yellowstone waking up. The actual volcanologists keep saying the same thing. It isn’t.

What You Should Actually Think

Yellowstone is fascinating precisely because it’s active. The earthquakes, the geysers, the thermal pools, the rising and falling ground, all of it means the volcanic system is doing what volcanic systems do. But doing something and preparing to explode are different things. The scientists monitoring Yellowstone have access to better instruments and more data than ever before, and they consistently report that activity remains at background levels. If that changes, they’ll say so. Until then, the ticking time bomb narrative serves media companies more than it serves anyone trying to understand what’s actually happening beneath America’s first national park.