In recent decades, we have come to realize the powerful effect that consuming excess sugar can have on our health. For this reason, non-nutritive sweeteners have blasted onto the scene. From “zero-calorie” soft drinks to diet snack bars and keto-friendly baked goods, alternatives like sucralose, aspartame, stevia, and erythritol have flooded the market. They promise consumers sweetness without the metabolic cost. For this reason, consumers, health professionals, and major food manufacturers have embraced these substitutes as a path to managing weight, controlling blood sugar, and achieving a healthier lifestyle – all while still being able to “indulge” in their favorite sweet treats.

Among these sugar alternatives, erythritol has emerged as a favorite. Unlike artificial sweeteners, it is a sugar alcohol that occurs naturally in some fruits and fermented foods. It is often promoted for its taste, which is remarkably similar to real sugar, and its minimal caloric impact. It’s a staple in many low-carb and ketogenic diet foods.

The Truth Behind Erythritol’s Sweet Promises

Image credit: Shutterstock

The promise of its guilt-free sweetness, however, is increasingly overshadowed by troubling research. A landmark study published recently in the Journal of Applied Physiology presents a powerful and potentially concerning finding. This popular sugar substitute may directly compromise one of the most vital, yet least understood, structures in the human body: the brain’s protective barrier. This new research provides a cellular mechanism explaining previously observed associations between erythritol consumption and an increased risk of severe health issues, including stroke. It suggests that a single, typical serving of an erythritol-sweetened beverage could expose the delicate network of brain vessels to a cascade of damaging effects.

For the millions of people who rely on erythritol to reduce sugar intake, these findings are critical. They force a necessary conversation about the actual cost of low- or zero-calorie sweetness and compel us to understand the complex biological systems we may inadvertently disrupt.

What is Erythritol? The Sweetener of Choice

To understand the study’s implications, we must first understand what erythritol is. It belongs to a class of compounds called polyols, or sugar alcohols. Chemically, it is a four-carbon sugar molecule. Its key characteristics are:

- Sweetness: It is roughly 60-80% as sweet as table sugar (sucrose).

- Calorie content: It is virtually calorie-free, clocking in at about 0.2 calories per gram. This is significantly lower than the 4 calories per gram found in sugar.

- Source: While it exists in trace amounts in foods like grapes, melons, and mushrooms, the erythritol used commercially is typically produced through the fermentation of corn starch by yeast.

- Metabolic profile: Erythritol’s primary appeal lies in how the body handles it. Erythritol is poorly metabolized by the human body. It is rapidly absorbed by the small intestine and then largely excreted unchanged in the urine. Crucially, this process means it does not spike blood glucose or insulin levels, making it highly attractive to people with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or those actively trying to lose weight by limiting carbohydrates.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved erythritol in 2001, and since then, its use has exploded. It is a fundamental ingredient in “sugar-free” candies, chewing gum, packaged goods, low-calorie soda, and other beverages.

However, its popularity has come with controversy. Prior epidemiological studies – research that looks for associations in large populations – have already rung alarms, suggesting a potential link between high circulating levels of erythritol in the blood and an enhanced risk of major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, such as heart attack and stroke. These earlier findings showed correlation, but they lacked a “smoking gun”; that is to say, a biological mechanism to explain why this link existed. The new study aims to provide that mechanism by focusing on the brain’s unique structure.

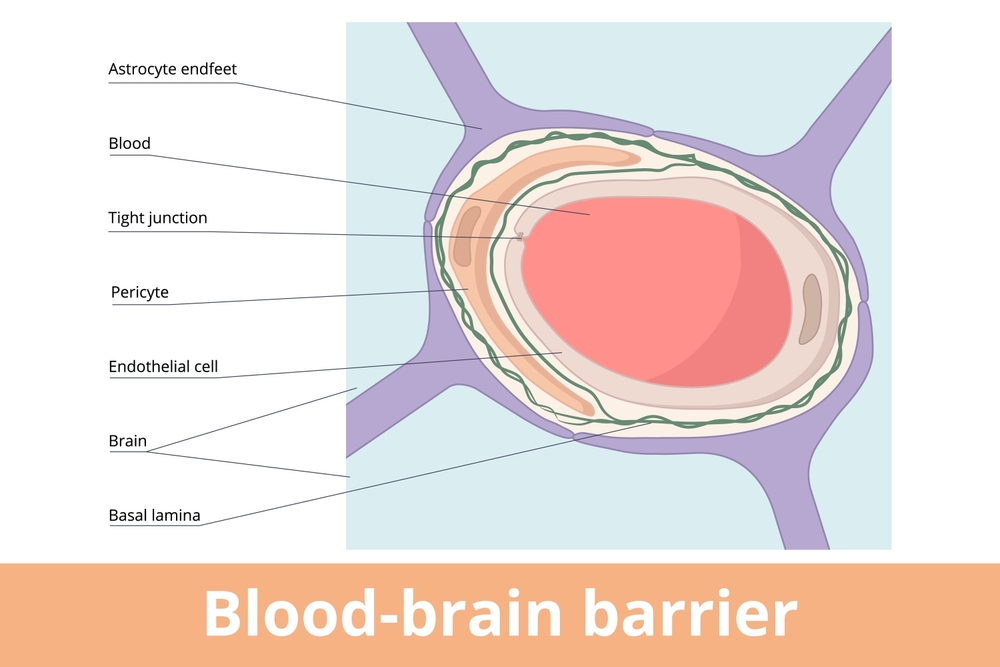

The Brain’s Great Wall: Understanding the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB)

The “brain’s protective barrier” mentioned in the study is scientifically known as the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). It is arguably the most crucial physical defense mechanism in your entire body, a sophisticated gatekeeper protecting the central nervous system.

Imagine your brain as a highly sensitive, secure fortress. It requires a constant, precise supply of nutrients, oxygen, and glucose, but it must be absolutely shielded from threats like bacteria, toxins, chemical fluctuations, and inflammatory cells circulating in the general bloodstream. The BBB is the structural embodiment of this security system.

How the BBB is Formed

The key components of the BBB are the specialized cells that line the inside of the brain’s microvessels; the tiny capillaries and arteries that penetrate the brain tissue. These cells are called cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMECs).

In most parts of the body, the endothelial cells lining blood vessels have small gaps between them, allowing substances to easily pass back and forth between the blood and tissues. The brain’s endothelial cells, however, are different. They are fused together by incredibly tight seals, known as tight junctions. These junctions act like molecular velcro, locking the cells together and forcing all substances to be actively transported through the cell bodies rather than passively leaking between them.

The BBB’s Critical Functions

The BBB has several important functions that keep your brain safe and healthy. These include:

- Physical protection: It blocks large molecules and pathogens.

- Chemical stability: It meticulously regulates the concentration of ions, amino acids, and other critical signaling molecules in the brain’s fluid, maintaining the perfect chemical environment for neural function.

- Vascular health: The health of these endothelial cells is paramount. When the BBB is compromised or “leaky”, the tight junctions degrade, allowing inflammatory molecules and potentially harmful blood components to flood the brain tissue, leading to inflammation, neuronal damage, and ultimately, contributing to diseases like stroke, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis.

The study in question focused specifically on the functional health of these very gatekeepers: the human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMECs).

Dissecting the Study: What the Scientists Found

Image credit: Shutterstock

The research, led by a team of physiologists, was designed to move beyond population-level associations and determine the direct, cellular effect of erythritol on the brain’s vascular system.

The Methodology: An In-Vitro Approach

To ensure a direct cause-and-effect relationship, the researchers utilized an in vitro (in glass, aka a test tube or a petri dish) model. They cultured human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMECs) in a laboratory setting. This allowed them to expose these specific brain barrier cells to erythritol in a controlled environment, isolating the cellular reaction from the complex variables of the human body.

The scientists administered a single dose of 6 millimolars (mM) of erythritol to the cell cultures. This dose was not chosen arbitrarily; it was calculated to be equivalent to the concentration of erythritol typically found in the bloodstream after consuming a standard, commercially available product containing approximately 30 grams of the sweetener. This is a highly realistic dose that many people are exposed to daily.

The cells were then monitored over a short period (3 to 24 hours) for changes in key markers of vascular health and function. The results were stark and provided a powerful biological explanation for the sugar substitute’s suspected health risks.

The Troubling Findings: How Erythritol Weakens the Barrier

The study revealed four major adverse effects, each contributing to a state known as endothelial dysfunction, which is a primary precursor to stroke and cardiovascular disease.

1. The Onslaught of Oxidative Stress

The first and most fundamental finding was a significant increase in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) production. This is a massive surge in what most of us call “free radicals” or, more simply, cellular oxidative stress. Researchers found that erythritol exposure caused ROS production in the hCMECs to increase by approximately 75% compared to untreated cells.

Oxidative stress is essentially “cellular rust.” While a small amount of ROS is normal, an excessive, uncontrolled spike overwhelms the cell’s natural defenses. The study noted that key antioxidant proteins (like SOD-1 and catalase) increased in the cells. This is a clear sign that the cells were struggling to detoxify the ROS surge. When this stress is unchecked in the brain’s endothelial cells, it directly attacks and damages the cell components and, critically, weakens the integrity of the tight junctions that hold the BBB together. Uncontrolled oxidative stress is a known pathway to BBB disruption and increased vascular permeability, allowing dangerous materials to leak into the brain.

2. The Loss of the “Traffic Controller” (Nitric Oxide)

The second finding concerned the body’s critical natural vasodilator, or blood-flow regulator, Nitric Oxide (NO). In the study, erythritol significantly lowered the production and bioavailability of NO.

Nitric Oxide is a key signaling molecule produced by the endothelial cells. It acts as the “traffic controller” of blood flow, instructing the smooth muscle surrounding blood vessels to relax (vasodilation), which ensures a steady, healthy supply of blood to the brain. NO also has a protective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-clotting effect. The study showed that erythritol inhibited the proper activation of the enzyme responsible for making NO (eNOS, or Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase). When NO production is reduced, the vessel’s ability to properly dilate is impaired, leading to a state of endothelial dysfunction that heightens the risk of acute cerebrovascular events and stroke due to poor blood flow.

3. The Rise of the “Constrictor” (Endothelin-1)

Complementing the decrease in the relaxing agent (NO) was an increase in a powerful constricting agent. The researchers found that erythritol induced a significantly higher production of Endothelin-1 (ET-1).

ET-1 is the most potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by endothelial cells. While NO encourages vessels to open, ET-1 encourages them to narrow. In a healthy vessel, NO and ET-1 are kept in a delicate, life-sustaining balance. Erythritol consumption appears to disrupt this balance, reducing NO while simultaneously increasing ET-1. This creates a state of chronic, unrestricted vasoconstriction in the brain’s microvessels, which significantly restricts cerebral blood flow. This disruption is a well-established pathological element underlying ischemic stroke development and severity.

4. Impaired Clot-Busting Capacity (t-PA)

The final key finding relates to the brain’s ability to defend itself against the formation of blood clots, a process called fibrinolysis. Erythritol-treated cells showed significantly impaired release of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) in response to a clot-forming stimulus (thrombin).

t-PA is a crucial enzyme that the endothelial cells release to dissolve fibrin clots. It is the body’s natural clot-buster and is, in fact, the active agent used in emergency treatment for ischemic stroke patients. By impairing the ability of brain endothelial cells to release t-PA, erythritol effectively reduces the vessel’s capacity to maintain its own patency and prevent thrombotic events. This directly contributes to a pro-thrombotic (clot-forming) environment, a major risk factor for stroke. Furthermore, impaired t-PA release is also independently associated with a weakened blood-brain barrier.

Read More: Doctor Claims These 5 Supplements Are Linked to Heart Attack and Liver Failure

Implications for Human Health and Future Research

Image credit: Shutterstock

The combined results of this study paint a clear, albeit concerning, picture: a single, common dose of erythritol is capable of inducing severe, multi-faceted damage to the foundational cells of the blood-brain barrier. In essence, the study provides the cellular link that explains the previous epidemiological association between high erythritol levels and increased stroke risk. The sequence of events is clear:

- Erythritol intake: A single serving creates a high concentration of erythritol in the bloodstream.

- Cellular attack: This concentration initiates massive oxidative stress in the brain’s endothelial cells.

- Vascular dysfunction: This stress leads to a pathological state of reduced vessel opening (less NO), increased vessel narrowing (more ET-1), and impaired clot-dissolving ability (less t-PA release).

- Increased risk: This dysfunctional environment creates the perfect storm for a cerebrovascular event like an ischemic stroke, where a blood clot blocks blood flow to the brain, or for long-term cognitive damage due to chronic BBB compromise.

It is important to acknowledge that this study was conducted in vitro, meaning in a petri dish, not in a living human or animal. The complexity of the human body’s metabolism and regulatory mechanisms, including how quickly erythritol is cleared by the kidneys, may influence the final in vivo effect.

However, the findings are robust enough to warrant caution and urgently call for further investigation. Researchers must now focus on human intervention trials to measure the chronic effects of regular erythritol consumption on indicators of endothelial function and BBB integrity. The question is no longer if erythritol can affect vascular cells, but how often and how much is required to induce permanent, pathological changes in a living person.

The Bottom Line

The search for a perfect sugar substitute is understandable, but the findings on erythritol serve as a powerful reminder that “natural” and “zero-calorie” do not automatically equate to “harmless.” The recent study provides a compelling mechanism showing that a popular sugar substitute may directly compromise the brain’s most vital defense system. By fueling oxidative stress, hindering natural blood flow regulation, and impairing the body’s ability to prevent clots, erythritol transforms from a benign sweetener into a potential vascular disruptor.

For consumers, the takeaway is not panic, but awareness. Given the serious implications, which include a potential increased risk of stroke, it is prudent to view erythritol-containing products with caution. Until further long-term human studies can clarify the full extent of this risk, individuals, especially those already managing pre-existing risk factors for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, should consult their healthcare providers about minimizing their intake. The true path to sustainable health doesn’t like in swapping one refined substance for another, but rather in moderation, balance, and a renewed respect for the fundamental integrity of our biological systems.

A.I. Disclaimer: This article was created with AI assistance and edited by a human for accuracy and clarity.