California air quality is always changing. People hear “air quality alert” and think it is just another notification, until the air tastes dry, your throat feels scratchy, and the sky looks washed out even at midday. In mid December 2025, parts of Northern California were told to stay indoors because fine particle pollution, known as PM2.5, climbed into unhealthy territory on the Air Quality Index. The warning focused on specific communities, including Portola, Sattley, Cromberg, and nearby areas such as parts of the Plumas National Forest and Sierra Valley, with AirNow readings showing elevated PM2.5 late on December 13.

If you’re not sure why that is important, I can explain. PM2.5 is the kind of pollution that slips past the body’s usual defenses, so you can feel “off” even without seeing thick smoke.

The headline might sound dramatic, but the point is straightforward, when the AQI reaches unhealthy levels, staying indoors cuts your exposure quickly, especially for kids, older adults, and people with heart or lung conditions. California has also had much larger air quality events than a few towns, so these alerts often remind people of past days when smoke and haze spread across whole counties and the “stay inside” guidance became a statewide habit.

What PM2.5 Is, and Why AQI Numbers Change Your Day

PM2.5 refers to particles 2.5 micrometers across or less, which is tiny enough to travel deep into the lungs instead of getting caught in your nose or throat. The AQI turns that invisible problem into a number people can use, because “bad air” is too vague to plan around when you have work, school drop offs, or an outdoor job. In the December 2025 advisory covered by Newsweek, AirNow reported AQI values reaching the 150s in the affected area, which falls into “unhealthy” on the standard scale. The same scale also explains why officials do not treat every alert the same, since “good” air sits in the 0 to 50 range, and truly dangerous situations rise into much higher categories where everyone is expected to avoid outdoor activity.

PM2.5 is widely treated as a high risk pollutant because the smallest particles can contribute to respiratory irritation and can also affect the cardiovascular system when exposure is high or prolonged, with the risk rising for vulnerable groups. The practical takeaway is not to memorize the categories, it is to treat AQI as a decision tool, like checking heavy traffic before you leave, because one look can tell you whether a run outside is sensible or a fast way to feel miserable.

Why Northern California Can Spike So Fast

Some air pollution days are slow buildups, but others arrive like a switch flipping because the ingredients line up at once. PM2.5 comes from multiple sources that can overlap, including wildfire smoke, residential wood burning, vehicle emissions, and industrial activity, and the mix varies by region and season. In rural and mountain adjacent communities, smoke can drift in from fires at a distance, while local heating sources add their own particle load, and the combined effect pushes readings upward. Weather then decides whether that pollution disperses or lingers, and that is where inversions, light winds, and stagnant patterns turn a bad day into a stay inside day. Newsweek’s report tied the advice directly to elevated fine particle pollution in the atmosphere, which is the key point because PM2.5 is what drives many of the health focused warnings. When people feel confused by an alert on a day that does not look visibly smoky, it often comes down to the fact that PM2.5 is measured, not guessed, and the number can rise even when the horizon looks ordinary.

Staying Indoors Works, but Only If You Do It Right

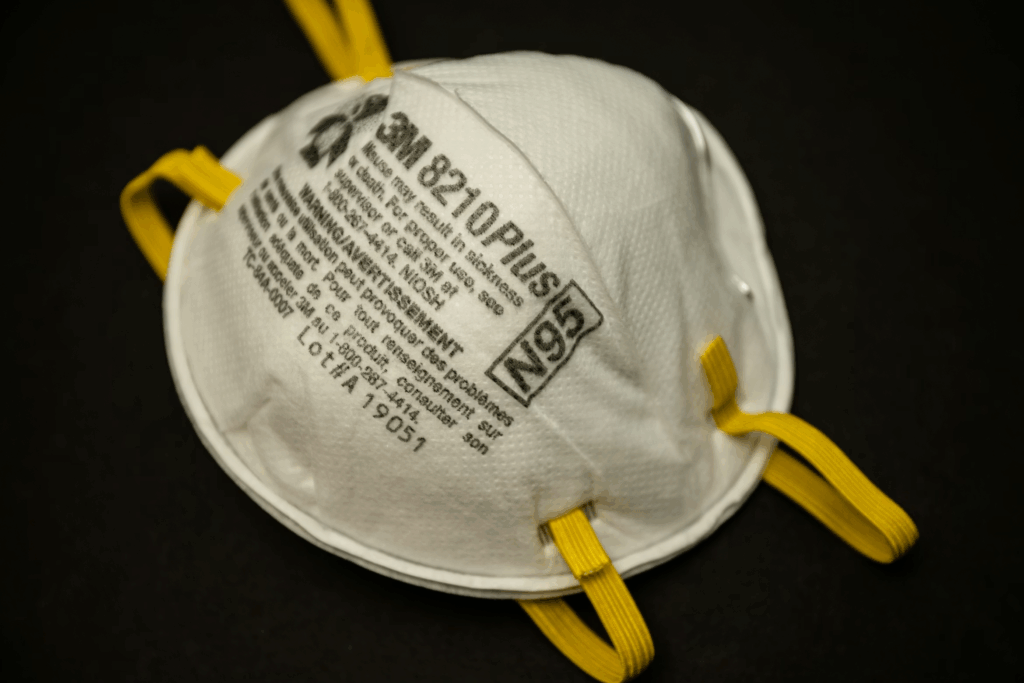

“Stay indoors” sounds straightforward, but plenty of people still end up breathing the same dirty air because of how they run their homes and cars. The simplest move is to close windows and doors and run air conditioning or heating on recirculate, because pulling outdoor air straight inside defeats the purpose. A HEPA air purifier helps, but so does upgrading HVAC filtration when the system can handle it, and the goal is to reduce fine particle levels in the rooms where you actually spend time. If you do not have a purifier, public health guidance during smoke events often points people toward clean air spaces like libraries, malls, or community centers with filtered air, since one well filtered building can lower exposure for many residents. When you have to go outside, expert guidance commonly recommends a well fitting respirator such as an N95 or KN95, not a loose cloth mask, because the mask needs to seal to filter fine particles effectively. Also watch what you do indoors, since frying, burning candles, and vacuuming without good filtration can raise indoor particles, so a “stay inside” day goes better when you keep indoor air as clean as you can.

Who Gets Hit First, and Who Cannot Simply “Stay Inside”

Air quality alerts are written for the public, but the impact lands unevenly, because not everyone has the same control over their environment. Children breathe more air relative to body size, older adults often have less respiratory reserve, and people with asthma, COPD, or heart disease can react quickly even at AQI levels that others shrug off. Then there are people whose work is outdoors, people commuting long distances, and people living in housing that leaks outdoor air, where “just stay inside” turns into a privilege rather than a plan.

During major wildfire events in Southern California, reporting has highlighted how exposed unhoused residents can be, because they are often forced to breathe smoke for hours with limited access to filtered indoor space and basic protective supplies. In those situations, distribution of respirators, access to clinics, and temporary shelter options become as important as the warning itself, because advice without resources leaves people in the same air with extra guilt layered on top. If you are helping someone who is vulnerable, the most useful support is practical: offer a ride to a clean air space, help replace a filter, share a properly fitting respirator, or check whether they have medication and a plan for worsening symptoms.

Similar California Episodes That Put Millions on Indoor Mode

California has a long memory for smoke days, so a localized PM2.5 alert instantly triggers flashbacks to the bigger events. In early 2025, severe wildfires in the Los Angeles area drove thick smoke across the region, and coverage described air quality advisories affecting roughly 17 million residents, with officials warning people to stay indoors and limit exposure. Those episodes carry additional risk because smoke is not only burnt vegetation, it can also include pollutants from burning buildings, vehicles, and household materials, which raises concern for respiratory and cardiovascular effects. Reports from that period described unhealthy to hazardous AQI readings in parts of the region, along with basic protective guidance that has become familiar in California: close up the house, run filtration, and use a respirator when you have to be outdoors.

Northern California sees its own versions, including advisories when wildfire smoke drifts into the Bay Area, where even moderate pollution can affect sensitive groups and change outdoor plans for schools and sports. The pattern across these events is consistent: the public message gets louder when the numbers rise, because exposure is cumulative across the day, and the fastest way to cut dose is to change where you breathe. That is why a December alert for a few communities still lands with statewide intensity, because Californians have lived through the weeks when the advice covered far more than one corner of the map.

The Fog Story Connects More Than People Expect

The Guardian’s December 13, 2025 reporting focused on a huge fog formation over Central California, including tule fog lingering across the Central Valley for weeks, documented by NASA satellite imagery. Fog is not the same as smoke, but the weather mechanics overlap in a way that matters for air quality, because the same inversion setup that traps fog can also trap pollutants near the surface. In the Guardian account, tule fog formed in November and persisted into early December, with explanations that included colder, moist air near the ground, lighter winds, and warmer air above acting like a cap that keeps the low cloud layer from lifting.

That “cap” effect is exactly why some communities wake up to stale air that does not clear by midday, and why pollution can stick around even after a source event ends. The article also described fog pushing toward the Bay Area via the Carquinez Strait, which is a reminder that what starts in one region can drift and change conditions elsewhere, including temperature and visibility. When people hear “stay indoors” for PM2.5 and then see weeks of tule fog on satellite images, they are seeing two versions of the same broader theme, which is weather that holds the lower atmosphere in place and limits how quickly the environment can flush itself.

Read More: Why Some People Prefer Staying Home: The Psychology Explained

Build an indoor air setup before the first alert

The goal is simple, make indoor air better than outdoor air before the first warning hits your phone. Pick one main room, usually a bedroom or living room, and treat it like your base for the day. If you have central heating or cooling, set it to recirculate and use the best filter your system can handle, many homes do well with a higher rated filter like MERV 13, but stay within the limits of your unit. Keep two spare filters because stores sell out quickly, and save the filter size in a notes app so you can reorder in minutes. If you use a portable HEPA purifier, run it continuously during the event, and keep doors mostly closed so it is cleaning a smaller area.

Wipe or vacuum the prefilter weekly during heavy smoke, and follow the manufacturer timeline for replacing the main filter, because a clogged filter moves less air and helps less. Reduce indoor particle sources on alert days, skip candles, avoid frying, and delay vacuuming unless your vacuum has good filtration. Most smoke episodes last from a day to several days, so your setup should be able to run without you babysitting it, and it should feel sustainable for the household, not like an all day project.

Protect your lungs when you have to go out

Sometimes you still have to leave, work, school pickup, medical appointments, or caring for someone who cannot be left alone. In those moments, a well fitting respirator does more than any other single step to cut how much PM2.5 you inhale. Keep several N95 or KN95 masks in your car and by the door, stored in a clean, dry bag so they do not get crushed or damp. Put it on before you step outside, press the nose bridge, and check for leaks by breathing out sharply, air should not rush around your cheeks. If you have facial hair, the seal usually fails, so plan around that, either shave or rely more on indoor time and reduced exertion. Replace the mask if the seal stops holding, it gets wet, it tears, or breathing becomes noticeably harder, during heavy smoke some people go through one per day. In the car, set ventilation to recirculate and consider replacing the cabin air filter on schedule, because you spend a lot of time breathing whatever your car pulls in. After you get home, change clothes if you were outside for a while, and rinse your face and hands, it keeps residue from getting tracked onto bedding and upholstery where it can reenter the air later.

Use a repeatable alert plan for symptoms, kids, and pets

Bad air days drain energy because every task comes with a new question, so set rules you follow automatically. Check the AQI for your exact area, then choose triggers, for example, at “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” kids and pets stay indoors and you run filtration in the main room, and at “unhealthy,” you cancel outdoor workouts and wear a respirator outside. Keep an alert kit in one spot, spare masks in multiple sizes, a thermometer, saline spray for irritated noses, and any asthma medication or inhalers where you can grab them fast. If someone in the home has heart or lung conditions, write down their red flag symptoms and the clinician’s after hours number, because smoke can escalate cough, wheeze, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

Plan for pets too, shorter potty breaks, no running at the dog park, and keep litter boxes and odor sources managed so you do not add irritants indoors. For multi day events, decide which errands are truly necessary and bundle them into one trip, it reduces exposure and keeps your indoor air working for you. Also identify one or two backup places with strong filtration, a library, a friend’s home, a workplace office, so you are not scrambling if your home setup is limited. The plan lasts as long as the event lasts, and it holds up best when everyone knows the rules ahead of time.

When the Air Turns on You

California’s hazardous air days, whether driven by smoke, elevated PM2.5, or weather that traps pollution near the ground, all land in the same place, your lungs and your routines. The main thread through this article is that the AQI is not background noise, it is actionable information that tells you when to change behavior before symptoms stack up. When you set up cleaner indoor air ahead of time, keep a respirator ready for the moments you have to step outside, and use a consistent plan for kids, older adults, and anyone with heart or lung risks, the warning stops feeling like a fresh crisis. The payoff is practical, fewer irritated eyes and throats, fewer asthma flare ups, and fewer avoidable trips into the worst air. California will keep having episodes like this, sometimes limited to a few communities and sometimes spreading across large areas, so the most useful response is preparation that works for a short spike and also for stretches that last several days.

Disclaimer: This article was written by the author with the assistance of AI and reviewed by an editor for accuracy and clarity.

Read More: The U.S. Cities That Theoretically Could Face the Highest Risk in a Nuclear Emergency