Scientists have found a 65,000-year-old tar-making site created by Neanderthals in Vanguard Cave, part of the Gorham’s Cave complex in Gibraltar, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Using a dating method that measures how long quartz crystals have been in darkness, researchers placed the site between 67,000 and 60,000 years ago. This was before modern humans reached Europe, when these prehistoric humans were the only human species in the region.

Thirty-One Minds Solving One Mystery

The work involved 31 scientists from six countries across 15 different fields, including plant studies, archaeology, geology, chemistry, and ecology. This team effort helped them understand the method Neanderthals used to make tar. It also shows the importance of working across disciplines when studying ancient technology. Their combined knowledge helped build a clear understanding of how the site was used.

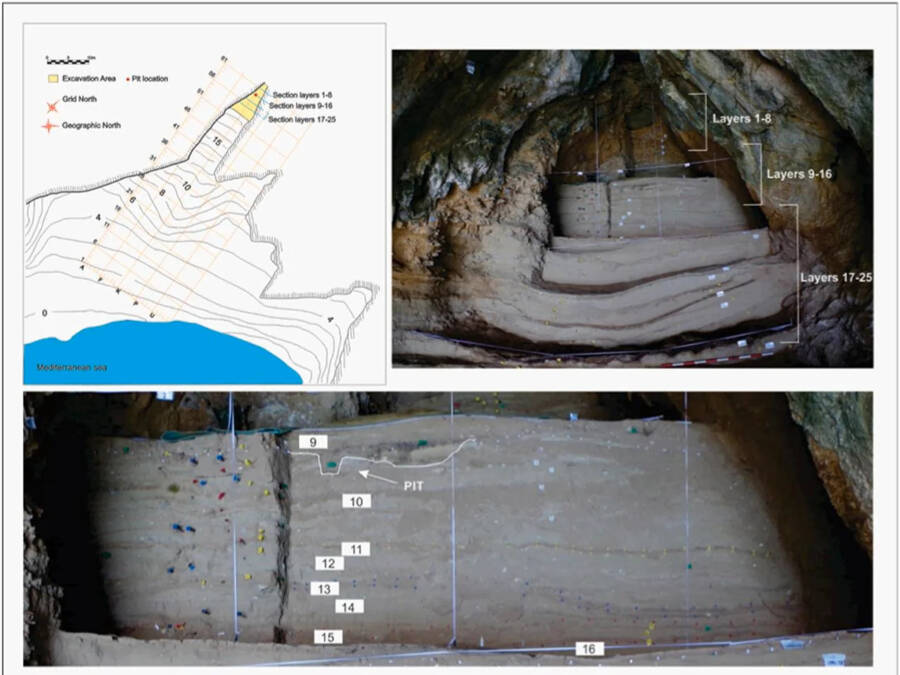

A Tiny Pit That Rewrote Human History

The hearth is a small round pit about 8.7 inches wide and 3.5 inches deep.. It has straight walls and two short trenches on the sides. Researchers believe this design helped control airflow and heat, both needed for making tar in low-oxygen conditions. The site also contained traces of ash, charcoal, possible tar crystals, and elements like zinc and copper. These suggest prehistoric humans may have sealed the hearth using bat droppings and sand to create the right environment for tar production.

The Clues Hidden in Ancient Dirt

Scientists studied the heart’s dirt using chemical and microscopic tools. They found substances like levoglucosan and retene, which form when resin-rich plants burn. The charcoal showed that the fuel came mostly from rockrose plants, which were common in the area. There was little use of pine or fir. These plants produce a sticky resin called labdanum, which was likely used to their advantage. Their choice of materials reflects familiarity with local plant properties.

The Smart Choice of Sticky Plants

The first known use of tar goes back 190,000 years in Italy, where flint tools were found with birch tar. So this new find is part of a longer story. Birch was rare in southern Europe, but rockrose was everywhere. This shows that they adapted their methods based on their surroundings. They used what was available and used it well.

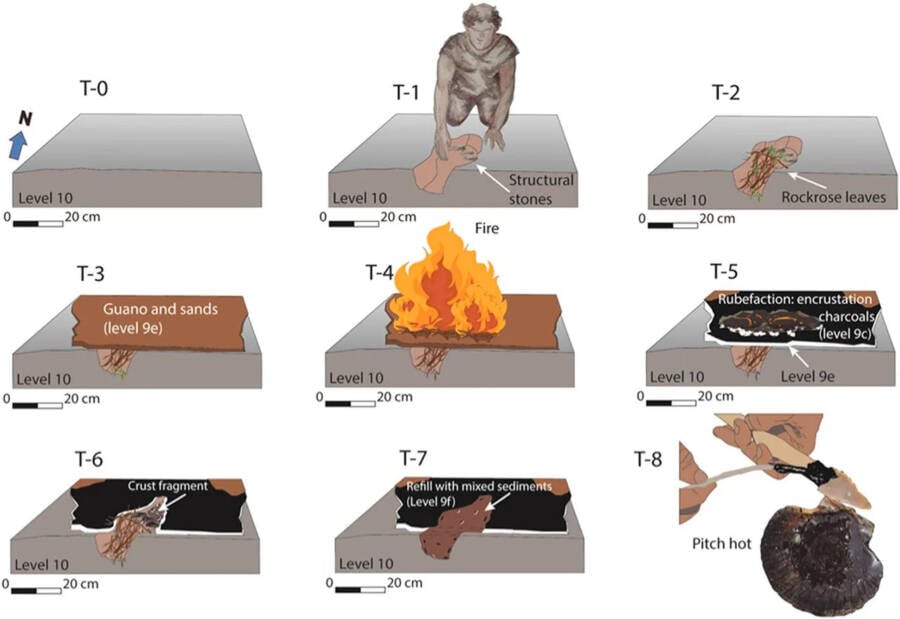

Turning Leaves Into Liquid Gold

At this site, Neanderthals chose rockrose because it was easy to find. Making tar meant heating plant material without letting it catch fire. They buried wood fragments and heated them with twigs, keeping the fire at about 150 degrees Celsius. The flames had to be carefully managed so the sealed leaves didn’t burn. This shows how they controlled heat while keeping oxygen out. It’s a process that needs attention and consistency.

When Scientists Played Ancient Chemist

Dr. Luis Ochando and his team tested their theory by building a replica hearth in Portugal. They filled it with young rockrose leaves and sealed it with sand and soil. Then they lit a small fire using grass and rosemary wood. The materials and methods matched what these ancient humans likely used. Their hands-on work helped confirm how the tar-making process might have worked thousands of years ago.

It Worked After 65,000 Years

When they opened the hearth, they found hot leaves covered in sticky resin. The black tar matched samples found at the original site. They used it to attach two flint arrowheads to wooden shafts and made working spears in a few hours. The experiment proved the method was effective and showed that the materials available to these prehistoric humans could produce reliable tools.

Why Two Heads Were Better Than One

Running the fire and collecting the tar took teamwork. One person managed the flames while another prepared materials. This cooperation suggests Neanderthals could plan together and carry out tasks that needed shared focus. The process involved coordination and trust. The knowledge was likely taught, practiced, and refined within their groups.

Read More: Underwater Discovery Reveals 6,000-Year-Old Bridge Linking Ancient Lands

Neanderthals Beat Us to the Punch

This tar-making method appeared over 20,000 years before modern humans used it. It involved knowledge of fire, plants, timing, and airflow. The technique was likely passed down through generations. It shows that they were not simply reacting to their environment-they were actively shaping it through practical knowledge.

The Sticky Stuff That Made Deadly Spear

Tar made it possible to attach stone tools to wooden shafts. Their spears were stronger and more effective for hunting animals like wild horses, woolly rhinoceroses, cave lions, and mammoths. The adhesive helped the weapons hold together through impact. Without tar, their weapons would have been far less reliable. Their hunting ground stretched about 2.8 miles from the cave, in what is now a submerged coastal area. Moreover, it was rich in wildlife like red deer, ibex, wild horses, ancient cattle, and wild boar. Tools and bones found in the cave show it was a thriving hunting site. The range of animals points to a diverse and resource-rich landscape.

Not Everyone’s Buying This Story

Some researchers remain cautious. Patrick Schmidt agrees the fire was real, but questions whether they used it for making tar. Christopher Scott suggests the resin served other purposes, such as waterproofing, medicine, or scent. Despite strong evidence, the debate continues. Further studies will help clarify the resin’s true purpose.

Time to Toss the Caveman Stereotype

The research shows Neanderthals had strong fire skills and problem-solving abilities. They planned, adapted, and created useful tools with care. These findings challenge the old view of prehistoric humans as simple and show a species capable of more than we once thought. Their story is still unfolding, but it’s clear they were not just surviving-they were innovating.

Read More: Ancient Cave Discovery Challenges Long-Held Beliefs About Australia’s First Inhabitants