Bacon, ham, hot dogs, and salami can be found in many people’s weekly shopping baskets. Yet scientists are urging tougher action because of the associated cancer risks. In late October 2025, UK experts renewed calls for cigarette-style bacon cancer warnings on food, or a phase-out of nitrite preservatives. This push arrived a decade after the World Health Organization’s cancer agency classified processed meat as carcinogenic to humans. People are asking what has changed recently and what the real risks are. In this article, we will attempt to translate the latest science into accessible language, compare positions from authorities, and offer practical steps that you can take. You will see where experts agree and where debate remains on this subject. The aim is not to scare you from your favorite foods, but to help you make informed choices regarding processed meats and cancer.

Why Are Ham and Bacon Cancer Warnings in the News Again?

On 24 October 2025, UK scientists and clinicians urged Health Secretary Wes Streeting to mandate cancer warnings on bacon and ham. They argued that nitrites and the resulting nitrosamines increase colorectal cancer risk, while many consumers still remain unaware. The Guardian reported estimates of tens of thousands of bowel cancer cases over ten years tied to processed meat intake, plus large NHS costs. The popular publication PEOPLE also covered the same letter for a broader audience, highlighting calls to phase out nitrates or use stark bacon cancer warnings on food, similar to tobacco.

However, the Department of Health’s response suggested that evidence on nitrites is still being weighed. This renewed push for changes follows summer reporting that popular Wiltshire ham still contained nitrites a decade after the WHO warning. Therefore, the issue resurfaced with more of a policy-driven edge, and not just your usual diet tips. Ultimately, it is about labels and the food industry’s processing choices.

What Is Considered Processed Meat?

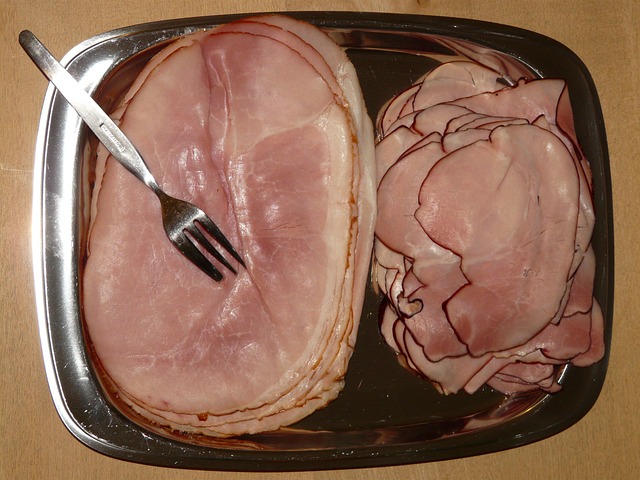

Processed meat is meat that has been transformed through salting, curing, fermenting, smoking, or other methods that improve preservation or taste. Bacon, ham, hot dogs, salami, pepperoni, and many deli slices fit this category. Nitrite salts are often used because they keep that familiar pink colour and add a cured flavour. Crucially, they also help suppress dangerous bacteria like Clostridium botulinum. However, nitrites can react with amines in meat to form nitrosamines. This is especially true when meat is cooked at high temperatures. Scientists have measured a range of nitrosamines across meat types, with NDMA among those most often reported.

Not all processed meat uses nitrites, since nitrite-free products exist, yet they remain a minority on most shelves. Regulators weigh food safety benefits against long-term cancer risks. That balancing act is why this conversation remains rather complicated, even as the evidence for colorectal cancer risk is growing. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that processed meat causes colorectal cancer in humans. It placed processed meat in Group 1, which signals strong evidence for causation. However, the WHO page clarifies that Group 1 reflects evidence strength, not that bacon is as dangerous as smoking per gram.

The World Cancer Research Fund independently reviews global data and advises eating little, if any, processed meat, because the link with bowel cancer is strong. The NHS advises cutting down if you eat over 90 grams a day of red and processed meat, and suggests aiming for 70 grams. These positions have remained consistent through recent updates. Therefore, despite ongoing debate about labels, the fundamental guidance is pretty steady. Eat less processed meat overall, limit red meat to moderate amounts, and build meals around vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fish or poultry when possible.

The Link Between Processed Meats and Cancer

Scientists have proposed several overlapping mechanisms. Nitrosation can produce N-nitrosamines during processing, storage, and cooking, while stomach conditions can also promote endogenous formation. These compounds can damage DNA and increase mutations. Haem iron in red meat may further catalyse nitrosation and cause oxidative stress in the gut. High-temperature cooking can add heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, though those pathways feature more prominently in red meat discussions. Recent European assessments flagged nitrosamines across multiple foods, not only meat, and set extremely cautious reference margins because these compounds are genotoxic.

Cancer Research UK explains these mechanisms for the public, underscoring that risk increases with amount and frequency. Biology is not a single switch, yet dose and pattern matter. Consequently, cutting down helps. Mechanisms fit the epidemiology, which repeatedly links higher processed meat intake with higher colorectal cancer risk. IARC highlighted a risk estimate often quoted in the press. Eating 50 grams of processed meat daily is associated with about an 18 percent relative increase in colorectal cancer risk. Harvard’s explainer puts that in plain terms. The average person’s lifetime colorectal cancer risk might rise from roughly 5 percent to about 6 percent with that daily habit.

The extra risk is meaningful at the population scale, yet it remains far smaller than the risk from smoking. Cancer Research UK stresses that any reduction can help, because the risk rises with the amount and frequency. The NHS uses simple thresholds to guide choices at the table. If your daily intake often exceeds 90 grams of red and processed meat, you should consider cutting back to around 70 grams. That change can come from smaller portions, fewer cured options each week, or swaps to fish, beans, or poultry in sandwiches and suppers.

Cancer Research and Policy Debates

Scientists who signed the October 2025 letter argue that warnings would inform shoppers at the point of purchase. They also urge the government to push the industry toward nitrite-free curing. Advocates point to public ignorance of the Group 1 classification and cite health costs. Critics worry that simple labels could overstate personal danger when occasional intake carries a lower absolute risk. The World Cancer Research Fund supports strong dietary guidance, yet it has not formally campaigned for cigarette-style warnings. Government departments note uncertainties over nitrite sources and complex exposure routes, including endogenous formation.

Meanwhile, the Food Standards Agency continues to assess nitrite and nitrate safety. It also tracks research showing how cooking and recooking can influence nitrosamine formation. Therefore, policy may blend improved guidance, better school and hospital procurement, and reformulation targets that reduce nitrite use without compromising food safety. Cancer Research UK’s 2024 explainer pulls together mechanisms and risk numbers in a reader-friendly way. It explains that processed meat is firmly linked to bowel cancer, and that risk grows with the amount and regularity. The charity avoids sensational language, which helps people plan small, realistic changes.

It also frames meat reduction as part of an overall healthy lifestyle, which includes weight management, moving more, and eating more plants. Those habits support better metabolic health and reduce cancer risk more broadly. You can still enjoy bacon occasionally, yet you should not treat cured meat as an everyday staple. That framing aligns with WCRF and NHS advice, and it gives families an achievable path. Small swaps and fewer servings per week add up across a year, particularly when paired with fibre-rich foods that support a healthier gut.

Practical Choices and Where Things Remain Uncertain

Start with frequency. If bacon or ham appears most mornings, try limiting it to weekends. If you buy deli meat for sandwiches, consider chicken breast you roast at home, tinned fish, hummus, or bean spreads. If you love full English breakfasts, add tomatoes, mushrooms, or baked beans, and reduce cured portions. Cooking methods matter a lot, too. Lower and slower cooking reduces charring and smoke, which lowers some harmful compounds. Portion size helps immediately. The difference between two rashers and one adds up across a month. Fibre supports a healthier gut environment, so bring in whole grains, lentils, fruit, and vegetables. Those foods support a diverse microbiome and shorter transit times, which may reduce carcinogen contact with the bowel lining.

Finally, it is important to read labels. Nitrite-free lines exist, yet check sodium and saturated fat. Health is not a single nutrient, so look at the whole meal pattern as you make swaps. Scientists still study how much nitrosation happens inside the body relative to preservatives added from outside. New work has explored how recooking shapes nitrosamine formation and how different curing methods compare. Regulators in Europe have reviewed nitrosamines in several food categories and continue setting conservative safety margins because these compounds damage DNA.

Researchers also examine whether dietary patterns change risk from the same meat intake, since fibre and calcium can influence gut chemistry. Therefore, two people eating similar bacon may not experience identical risks if their overall diets differ. However, the central point still holds. Across decades, higher processed meat intake repeatedly tracks with higher colorectal cancer risk. Mechanistic studies explain why that association appears. Practical advice remains to reduce frequency and portion size, since those steps lower exposure while keeping meals enjoyable. Progress will likely come from both home kitchens and industry reformulation.

Schools and Public Kitchens

It is easier to choose alternatives when budgets and time allow. Many families rely on inexpensive lunch meats for quick sandwiches. Policy can support healthier defaults in places where many meals are served. Public procurement standards can shift menus in schools, hospitals, prisons, and government offices toward lower processed meat options and higher-fibre choices. WCRF encourages settings to model healthier patterns rather than rely on labels alone. That is significant because taste tracks exposure. Children who get used to savoury, salty cured meats may prefer them later.

Menu teams can honour culture with satisfying stews, roasted poultry, beans on toast, and vegetable-rich dishes. Retailers can also help by stocking clear nitrite information and expanding nitrite-free lines at affordable prices. Over time, those nudges change baskets without shaming customers. People deserve safe food and simple guidance that fits real budgets and real lives. Another lever is kitchen training and equipment, because even the best intentions fail without the proper tools. Many school and hospital kitchens rely on reheating, yet simple gear like combi-ovens, slicers, and steamers lets staff serve roast chicken, lentil stews, and veg-heavy tray bakes at scale.

Procurement can bundle ingredients and training, so cooks learn speedy batch recipes that cost less per portion than ham rolls, yet taste better. Community programs can help too: Tuesday “cook once, serve twice” classes show parents how to turn a whole chicken into sandwiches, soup, and a rice dish, so lunches stay quick but less processed. Retailers can back this with multi-buy offers on beans, frozen veg, and wholegrain wraps. Small, practical upgrades make healthier defaults easier, cheaper, and popular.

Comparing the UK debate with global guidance

Globally, guidance is strikingly consistent. WHO explains that processed meat is a cause of colorectal cancer and that risk rises with dose. WCRF recommends little, if any, processed meat and moderate red meat. Cancer Research UK and NHS echo those positions in UK-specific language, adding simple portion advice. Where countries differ is in labels and procurement rules. Some municipalities use warning icons for high-sodium foods. Others push voluntary reformulation. The current UK debate brings tobacco-style labels into focus, yet that step is not universally endorsed.

The practical core remains stable across borders. People benefit from eating less processed meat, choosing more plants, and keeping red meat moderate. Therefore, while policy headlines may vary, the everyday plate changes look similar in many places. Shoppers do not need to wait for a label to start benefiting from gradual swaps. Some countries are testing stronger nudges that go beyond simple dietary advice. In parts of Latin America, front-of-pack warning symbols help shoppers spot high salt or saturated fat quickly.

Canada’s dietary guidance shifted toward patterns, placing less emphasis on processed meats and sugary drinks. Several European cities use procurement standards that cap cured meats in school meals. Supermarkets trial shelf tags that compare sodium and nitrite content within the same aisle. Workplace canteens quietly swap default fillings to roast poultry, tuna, or beans. These moves rarely ban foods, yet they shape what people see and choose. Therefore, culture stays intact, while the average weekly intake still drops. The common thread is steady, structural support that makes healthier habits the easier option.

The Bottom Line

Processed meat is convenient and tasty, yet the link with bowel cancer is strong. The most helpful changes are simple and repeatable. Cut back servings per week. Shrink portions on days you do eat bacon or ham. Bring in beans, whole grains, vegetables, and fruit. Roast a chicken for sandwiches. Choose fish more often. Read labels, since nitrite-free products exist, but keep an eye on salt. Cooking more gently helps. If you love cured meats, treat them like occasional treats rather than daily staples. That approach respects food traditions while protecting long-term health. It also aligns with guidance from WHO, WCRF, NHS, and Cancer Research UK. Policy may add labels or reformulation targets, yet your kitchen choices matter today. Small shifts add up across months, and they protect families without sacrificing pleasure at the table.

Disclaimer: This article was created with AI assistance and edited by a human for accuracy and clarity.

Read More: Country Leads the World in Rapidly Increasing Cancer Cases and Deaths